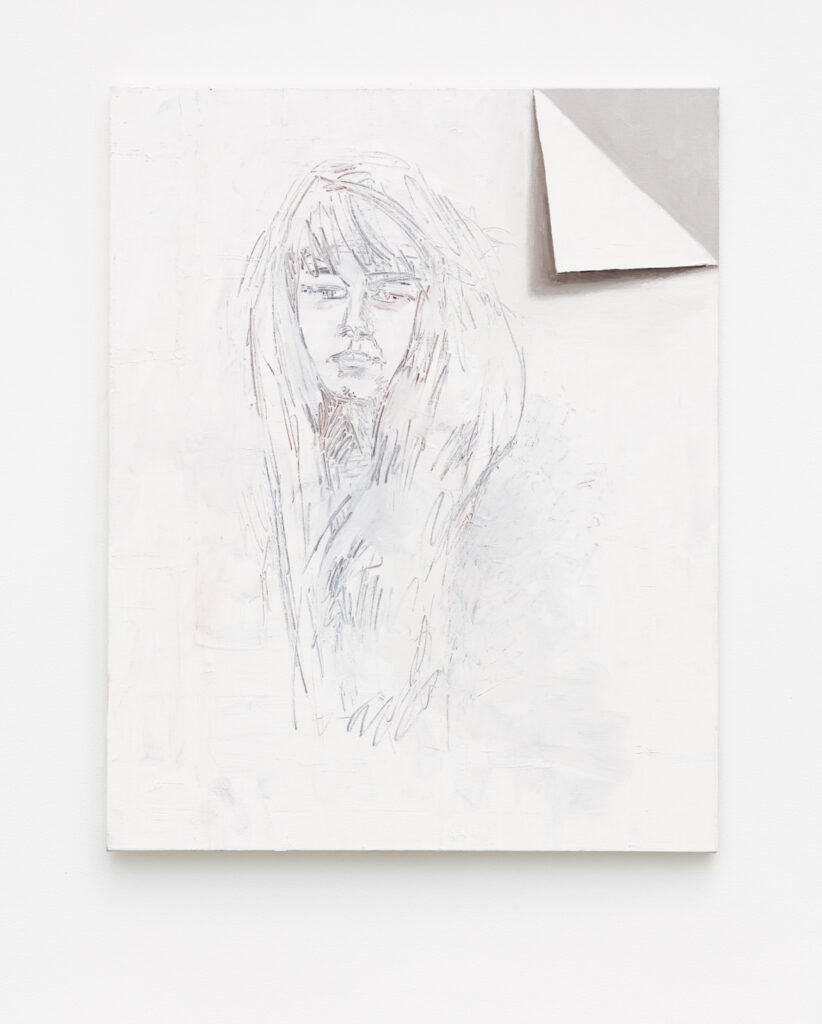

2022

16 x 16

Oil on linen

Sarah Sarchin is a painter. She makes work that is satisfying and enticing. She is an exacting worker, a wizard whose skill is never at the forefront. Recently she has been making work that uses shapely legs, brick walls, and Brigitte Bardot to divine and play with the relationship between womanness and paint. That’s maybe too general, but to be more specific would be a disservice to the work. – Ravi Jackson

Real-life conversation between Sarah Sarchin and Ravi Jackson that took place in Los Angeles on November 13, 2023, edited by Jonathan Pfeffer.

RJ: What kind of sandwich did you get?

SS: The Green Goddess Caprese Melt.

RJ: What are things that might influence your opinion of a sandwich?

SS: I think you have a more information-based approach to how you respond to food whereas I kind of feel it out.

RJ: Does that mean the mood you’re in can impact your experience of a sandwich?

SS: Well, while you might look up Panera Bread to find out what their deal is as a food franchise or to find nutritional information about this sandwich that’s come into your life, I’m inclined to be like, “What a great sandwich; it was free!” Maybe I’ll feel sick, maybe not. I’ve had a lot of these box lunches recently for my job. I’m becoming kind of a connoisseur of crappy box lunch offerings. As I go into it, I’m like, “I’m gonna get a shitty sandwich.” Within that kind of scale, there’s room to say “Oh, it’s not so bad.”

RJ: You’re grading it on a curve from the beginning.

SS: Right, I’m grading it on a curve.

RJ: Do you care to rank certain sandwiches or experiences with these catered lunches? Or are you saying it’s always satisfying because you get free lunch even if you’ve lowered your standards?

SS: It’s always not satisfying.

RJ: Satisfaction is not even a metric you use.

SS: I think about what makes a sandwich good. It’s pretty straightforward: you have bread, you have the fillings inside. The ingredients are important. How it’s assembled is important. I’ve noticed a pattern with these box lunches that they’re heavy on the sauces, like sometimes multiple sauces for one sandwich for some reason. They tend to use pretty greasy bread so you’re full even if you’re not satiated in a more meaningful way. But they’re always thrown together; you open the sandwich and it’s kind of like half in the bread, half on the paper. A bunch of juice is gonna fly everywhere when you try to eat it. Usually, someone is also giving a presentation while all this is going on. They always give you a bag of potato chips too, so you’re given this debacle of trying to counterbalance this super messy, sloppy wet bread situation with some loud potato chips while listening and taking notes.

RJ: Is it similar to the feeling of being the only person munching loudly in a quiet movie theater? Is there that kind of tension in the room between the speaker and the loud chewers in the audience?

SS: Yeah, I think we’re all just really interested in eating lunch and some poor person is up there giving their PowerPoint presentation. Even if that’s not happening, there’s the idea that we’re supposed to socialize, network, and build relationships during the entire period that we’re there.

RJ: It’s sort of like, “Oh, you also got the Green Goddess?”

SS: Exactly. “My name’s Sarah…”

I think I like it, actually. It’s a work training type of environment that’s outside of my life trajectory before now. I always feel like I’m an anthropologist going in and seeing how real work functions, how real people talk to each other in the workplace or something. But more recently I’m seeing this as part of a false idea artists have of their special position in society. In this situation, I think everybody there feels like it’s outside of their normal thing, and it’s a strange social situation to be thrown into. It’s kind of like we’re all choosing to do this thing together, that we’re also required to do together.

2022

20 x 20 in

Oil on Linen

RJ: I want to hear about your dream sandwich.

SS: Did you show me the TikTok video of the sandwich where everything’s chopped up first? It was a deli somewhere in Brooklyn, you go through and order a sandwich the same we’re used to – you know, “Ham, cheese, whatever, this, that.” They put all those ingredients onto the sheet of paper and then chop them all together into a really fine dice. They add mayonnaise and mustard, so it looks like coleslaw, but it’s actually whatever you wanted – turkey, cheese, etc. – the proportions are the same but the ingredients are cut up really small and evenly distributed. I suppose the appeal is that every bite is perfectly balanced because it’s got every single ingredient represented in it.

RJ: But wouldn’t that change the portion you need? I think you must need more mayonnaise to kind of hold it all together.

SS: Yeah, but it’s not necessarily a bad thing. There’s a burrito chain in Seattle when I was growing up and you’d get big burritos from them. It’s like Subway, but burritos. That was the really exciting thing.

RJ: Like Chipotle?

SS: This is before Chipotle but kind of a similar idea where you start at one end, they pull out the giant tortilla, then you tell them everything you want them to put in it as they slide across on the other side of the sneeze skirt thing, then they wrap it up. When I was in high school this restaurant hit the scene, it was a very exciting destination for suburban teenagers who are always hungry. My friend Andrew worked at the one by our high school. Andrew had a special technique that he developed where once he got to the end and all of your ingredients were in the tortilla, he would massage all the ingredients together by hand before closing the burrito.

RJ: Would he do that for everybody?

SS: I think it was the special friend treatment.

RJ: It sounds gross.

SS: Yeah, it looked awful but he wore gloves. He was all about how every bite had to have every single ingredient. You look like you’re going to throw up.

RJ: I’m okay. I think I might refuse the burrito after I saw that.

SS: Even with the gloves?

RJ: I don’t want somebody to massage my food before – okay, maybe ‘massage’ is the wrong word, but I don’t want to see it hand-mixed.

SS: “Hand-mixed”?

RJ: Which ingredients?

SS: Whatever you want. Since I was vegetarian it was beans, rice, and salsa. Cheese.

RJ: I’m seeing the cheese-gloved fingers…

SS: What if you started with a bowl, put all the ingredients you want in your burrito, stirred it with a spoon, and then spooned it into the tortilla?

RJ: That sounds fine.

SS: Okay, so you’re not opposed to the mixing, you’re just opposed to the hand-mixing.

RJ: I don’t want someone I know hand-mixing the ingredients. I also think there’s something nice about the kind of natural layering that you get in burritos. I’ve seen short videos about this sandwich you were talking about. Coleslaw is my frame of reference for what the texture or mixture would be. What I like about the burrito is that there’s room for you to get involved, too. Sometimes you’re going to get a bite that’s just like beans and salsa. Sometimes you’re like, “Oh, this is going to be mostly rice and cheese.” It feels like there’s kind of an interactive game that you play that’s kind of nice.

SS: If every bite is the same, then there’s no longer the possibility of a perfect bite?

RJ: I guess. I don’t know if I’m looking for the perfect bite, but there’s no possibility for surprise. Maybe I like surprises. Sometimes in a good sandwich or burrito, you get a really good bite where you get everything. “Ooh, I got a lot of pickled onion in that bite” – and I like pickled onions.

2022

30 x 24

Oil on Canvas

SS: If it’s a sandwich with a lot of bread or crust, I’m always awkwardly eating around the side of the sandwich because I want to save the middle bites for last, where there’s like the most non-bread-to-bread ratio.

RJ: Yeah, I think you save the best for last.

SS: Sometimes I do it just because I don’t want stuff to slip out of the sides.

RJ: You’re avoiding the question of what’s your dream sandwich.

SS: Well, I think the bread has to be fresh. I don’t want to say just one kind. Whatever kind, the bread has to be fresh and soft. Not too crunchy.

RJ: Do you toast it? Does it just depend on the bread?

SS: It depends on the bread and the sandwich. I think it’s more about each sandwich being good in its own genre. When I grew up in Seattle, the idea of a perfect sandwich at that time would have had sprouts, sunflower seeds, Tofutti cream cheese, and shredded carrots. It would be on this multi-grain sprouted bread with maybe seitan or some other kind of soy-based protein thing on it, some liquid aminos. Whereas now sandwiches consist of a really good baguette, a little bit of ham, some Swiss cheese, and Dijon mustard. Maybe that’s the perfect sandwich right now: maybe the ham and cheese. Just simple, elegant, each ingredient is good.

RJ: I feel like I’ve seen a lot of cheeseburgers where it feels like the argument that the restaurant’s trying to make is that this is a good burger because all the ingredients are really expensive or there are so many different ingredients. My favorite cheeseburgers for a long time now have been very, very simple. I just want good bread. Blue cheese and truffle aren’t going to make it better for me. But, is that it? Did we land on your perfect sandwich? Ham and cheese with the right amount of mustard?

SS: Maybe…

RJ: Well, you don’t have to pick just one. I guess I’m kind of the same way, like I’m kind of a purist. Would you say that that’s a purist attitude toward sandwich genres?

SS: Do you think it’s purist, or do you think our food preferences are so conditioned by where we live, the time that we live in, food trends, etc.?

RJ: Yeah, well like the Seattle sandwich you’re describing is kind of alien to me. Wraps were a big thing, but I think they were much bigger in Seattle?

SS: Yeah, Seattle was big on wraps. There was also the idea of good food being really complicated. I feel like we’re in kind of a new period of thinking about food where maybe good food is…not so complicated.

RJ: Authentic?

SS: Exactly. Somehow my idea of the ham and cheese sandwich is that it’s French. I’ve actually never been to France so I don’t know what a ham and cheese sandwich served to me there would be like. But in my mind, I’m like, “This is an authentic ham and cheese sandwich because it’s not American. It’s on a baguette and it has Dijon mustard.”

RJ: I think the big thing there is the ham and butter on a baguette.

SS: Darn.

2019

Oil on Canvas

24 x 20 in

RJ: Some friends of mine and my cousin got into an argument about whether chicken teriyaki qualified as legitimate Chinese food. I guess for the person whose favorite dish it was, he was saying, “Well, yeah, because you can order it at many Chinese restaurants.” I guess my take is that it doesn’t really matter that much. But should it matter? Should our perceived French-ness of a ham and cheese sandwich accentuate or diminish our enjoyment of it?

SS: I think living in a “food city” and being able to eat all the kinds of food we could eat right now, just an absurdly long list of restaurants with different regional cuisines, everything is conditioned by this idea of authenticity or purity before I even eat it. I haven’t been to China, but I have been to Alhambra [LA suburb]. Somehow that credentials me in my own mind to have an opinion about whether or not this food is legitimate or not. Then that tells me whether or not I think it tastes good.

RJ: It’s definitely a part for sure. I feel like people go to Dim Sum in Alhambra or a restaurant like Chengdu Taste that has a reputation of being more faithful to the cuisine from that region of China, which I have no way to judge at all. I’ve never been there but it still is a part of my experience with the relationship with the restaurant. It’s not something you can control, but I kind of feel like you should just enjoy it; we should be able to enjoy the food for what it is.

SS: So, how was your sandwich?

RJ: My sandwich was fine. Maybe it’s just because you used the word but I feel like that sandwich is designed not to be satisfying. I feel like they put an exact measurement, like it cannot exceed more than two ounces of beef…

SS: Do you think they’re using a scale for all the ingredients?

RJ: They probably are. I wouldn’t be surprised. At Subway, they use a specific little cup to dose them out. My sandwich did not have a sauce problem. Like you said, all these places have just way too much sauce.

SS: If you get anything with goddess in the title that should be a tip-off that it’s going to be a sauce-forward sandwich. I think the trick with these events is to not be the first in line to the sandwich table, but also not be the last. You kind of let everyone else read all the ingredients and choose their fate, then observe a few people open their sandwiches, then go over, make your choice before like the only one left is…I don’t know…”Tuna surprise goddess”?

RJ: Well, I think you have to follow the wisdom of the crowd. I guess to finish my assessment of my sandwich, it’s like 90 percent bread. There’s cheese baked into the bread. It’s like they added maybe a little bit too much cheese and it was just blasted through a furnace real fast. So, it goes from like room temperature to a thousand degrees for ten seconds, then it’s out. It just feels like an accumulation of different ingredients; it doesn’t get the time to like actually be together and kind of cook together. Relative to the bread, there’s barely anything there. The bread itself is very greasy; it’s covered in cheese and what feels like drizzled oil. I feel like it gives the image of decadence, but in reality, it’s like you eat a big mouthful of bread soaked in oil.

SS: How do you describe that? Is it a hoagie? It’s not sliced bread.

RJ: I guess it’s that form factor. It feels like it was invented by Subway.

SS: Well, when you open it, you’re like, “Whoa, huge sandwich!” There’s that moment of excitement where you’re like, “I am going to be full. This is great.” You go from a mystery box with so much uncertainty. You open the box – “Chips, cookie, I know this format” – you unwrap the sandwich, and you see the shape – “Okay, the sandwich is long-shaped, it’s not sliced this time, it’s like a bread roll format” – you unwrap it, and you’re like, “so much sandwich!” Then you get into it, and you’re like, “Ugh, so much bread.”

RJ: Is the shape of the sandwich appealing?

SS: I mean, it’s the shape of a baguette without the substance of a baguette.

RJ: And it’s not really like a baguette…

SS: It’s kind of like a weird focaccia…no, it’s like a ciabatta in the shape of a baguette.

RJ: Why do they do that? What is it supposed to signal?

SS: Well, there also must be some oven and ingredient calculation. Like, they can get maximum bread volume out of fewer ingredients.

RJ: I think you’re probably right. It has to do with the shape of a baguette. Do you think there’s phallic symbolism there?

SS: There’s definitely a “more is better” undercurrent in our food culture.

RJ: Are we sandwich size queens?

SS: Well, when I opened that Green Goddess Caprese sandwich today, I was like, “Yes, it’s huge.” So, maybe! [laughter]

RJ: Big queen penis sandwich. I imagine at the event you described earlier that the sandwich is the payoff.

SS: It feels hilarious that you’re in a room full of adults doing something you may or may not be getting compensated for, and then you get this lunchbox that has a big chocolate chip cookie. It’s always kind of messy, then they’ll have like the shitty coffee with the shelf-stable creamers. I’ll always get the coffee and eat the cookie after eating way too much sandwich. It does overcome whatever else is going on around the thing we’re all doing that day. You’re like, “I get to eat this cookie now.” There’s something that feels really juvenile about it, like school lunch.

RJ: You sit through the long meeting but then you get a very mediocre sandwich.

SS: And if you didn’t like the sandwich, you get a cookie! Then there’s this funny pile-up. Everyone has a whole box that their lunch came in, so at the end of the training, all of the garbage cans are stacked five feet high with empty boxes.

RJ: The boxes are really big.

SS: They’re like shoe boxes. I guess it’s because the sandwiches are so big.

2022

11 x 14 in

Oil on Canvas

RJ: We both teach. I feel like a lot of my students want to like or dislike a painting without thinking about it too much, even at a basic level. I try to give them the language that might enable them to articulate what they see beyond something they might enjoy like a cookie in the Panera Bread box. I want to give them permission to feel deeply about a painting or be surprised, enamored, or even hate something. I want them to have a strong reaction, whether it’s intellectual or emotional or physical that goes beyond, “I don’t like the red in that painting.” Then there are the savvier students who are more familiar with the vocabulary of interpreting art and see that direction as a way of currying favor and looking smart.

SS: I have this corny spiel I give my students the first time we do critique where I try to frame the idea of critique as a generous practice. The goal isn’t to talk about what you like or don’t like, but to try and address each thing we look at on its own terms. To talk about why it is or is not successful at being the painting that the artist wants it to be.

I think of it as generous because to some extent you have to put your own taste and subjectivity to the side, to be outside yourself and in the space of someone else’s goals and ideas. Hopefully, when we start talking about a painting, it isn’t theoretical. It’s like, “This isn’t a painting that I would make, but here’s what it looks like it’s about, and here’s how that’s working or not working.”

Outside of teaching, when I go and look at paintings I certainly have a lens between me and anything that I look at that includes all the effort I’ve put into my own visual literacy – that’s always going to exist. At the same time, my subjective self can still be displaced a little bit by an artwork; it’s still possible to be surprised, or taken in, or repulsed. And it’s not necessarily a physical thing, it can also be an intellectual thing. Like I don’t totally get this, but I like it.

RJ: Does it happen to you with any regularity? I think for me it happens less and less.

SS: I think it depends on how much art I’m seeing.

RJ: I do feel like I have to consciously switch modes of being like, “I’m not going to look at this in the way I might talk about it in a classroom. I’m just going to stay present.” I feel like there are a lot of times when I realize I’m not being present for the work just as a person looking at it and I have to turn off the switch. But then there were earlier moments when I was learning about art. I guess I was looking at a lot more art, but everything was new…

SS: When you first start plugging things into an art historical or contemporary art structure, you see things that make references and connect this whole new constellation of information, that’s thrilling. But as the dots connect, that thing happens less and less over time.

RJ: I feel like every time I would go to see a show, or a few shows at once, there was something new – or that was new to me – and I would react to it really strongly.

SS: When you’re in that phase, you are absorbing a huge amount of information that gives you access to all of the references that artists make in their work. It feels like you’re entering into a secret language or a specialized, coded language that is invisible unless you know those references. The more you look at stuff and file it away, the more this connection of all these different data points starts to really kind of come into high relief and be a real thing.

I shared with my students this painting by a contemporary artist – it’s a giant red painting of the interior of a room and the whole room is red. I was talking about how this could be a reference to Matisse’s Red Studio and several of the students were incredulous that this was actually a real reference being made here.

RJ: Do you think that makes it better? I definitely enjoyed learning about art history, but I don’t like the idea that that’s going to make the work better.

SS: I think it does in this particular painting I’m talking about. But yes, there’s the process of learning that whole language of visual references, then there’s the subsequent part where you have to contend with whether making a particular reference is productive or interesting or meaningful, or is it nothing.

It’s not like, “Ah now we’ve entered into the rarefied world of higher communication because I’ve seen some Matisse paintings and can identify all references to Matisse among contemporary artists.” Now we have to contend on an intellectual and emotional level with “What is this particular reference doing in this work that adds value?” I think when you’re new, everything seems equally important and interesting, then over time some artists I used to think were so exciting…

RJ: The bee’s knees.

SS: Yeah, the cat’s pajamas. Now I’m like, “Man, that’s not so interesting any more.” Certainly, artists who I remember seeing years ago and being like, “Okay, this person’s important, I guess, but I just don’t get it.” I’m like, “Oh, wow, this is just the bee’s knees.” It kind of finally clicks somehow 10 or 15 or 20 years later.

RJ: Do you have a memory of a sandwich that was so good that you ate it more slowly, or you felt like you had to appreciate it more?

SS: Are you asking this because I’m a fast eater?

RJ: That’s probably a part of it.

SS: I can’t think of a specific recent sandwich experience, but you’re putting a grilled cheese into my head.

RJ: Do you have a specific grilled cheese memory?

SS: Well, it’s just the grilled cheese of my youth, which is probably Orowheat brand 24-grain bread…

RJ: What kind of cheese?

SS: Tillamook sharp cheddar cheese. There’s much more cheese than there should be. There’s butter on the bread.

RJ: You don’t put the butter in the pan, you just butter the bread?

SS: Either works. I think you put the butter in the pan because the butter is too cold to spread.

RJ: That’s your sandwich.

SS: That’s the core memory grilled cheese.

Sarah Sarchin is a painter living in Los Angeles. Recent solo exhibitions include Veronica Project Space in Seattle, Grice Bench and Sean’s Room, both in Los Angeles, and the Chan Gallery at Pomona College. She received her MFA from the University of California, Los Angeles, and her BA from the University of Washington.

Ravi Jackson is a Los Angeles-based artist whose work uses imagery and text from popular culture as a way to negotiate ideas about race, art, and sexuality. Recent exhibitions include David Lewis Gallery, New York; Matthew Marks, Los Angeles; and PAGE(NYC), Petzel, New York. He received his MFA from the University of California, Los Angeles, BFA from Hunter College, and BA from Oberlin College.

Leave a Reply